Is the Phonograph a Musical Instrument?

A subsection of the Grinnell College Musical Instrument Collection, the Grinnell College Music Department Early Phonograph Collection, includes eight late-19th century and early-20th century analog (non-electronic, using physical linkage) phonographs along with hundreds of phonograms (re-playable objects containing encoded performances) in a variety of formats (two-minute cylinders; four-minute cylinders; both one-sided and two-sided 78rpm discs; and two-sided 80rpm discs) that were in use during the early decades of sound recording. A reasonable pair of questions to arise from the inclusion of these objects in the instrument collection is: “Are phonographs musical instruments?” and: “Are recorded performances equivalent to live performances?” While initially it might seem appropriate to respond negatively to both of these questions, we must at least acknowledge a few ways in which both record players and sound recordings are similar to the hundreds of other instruments presented on this website. For example, we say “I’m going to play some music on my phonograph (or computer or phone),” so both musical instruments and phonographs are “played” by individuals. We on occasion also say a recording “sounds live”, and it is not unusual for us, after repeated listening to a recording, to be let down when we then hear a live performance of the same music because it diverges in minute ways from the performance we’ve heard repeatedly on a recording. As it turns out, early recording companies went to great ends to convince the public that their machines are musical instruments and that the sound they produce is indistinguishable from what one hears in a live performance. They did this through advertising.

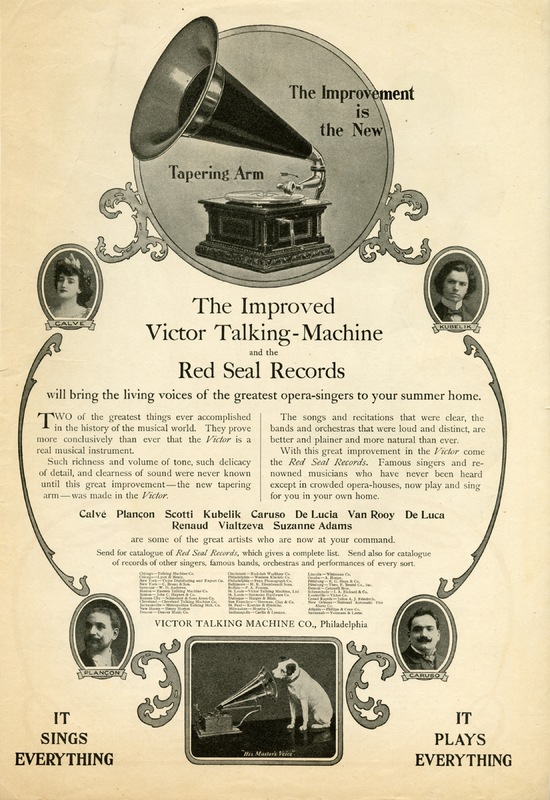

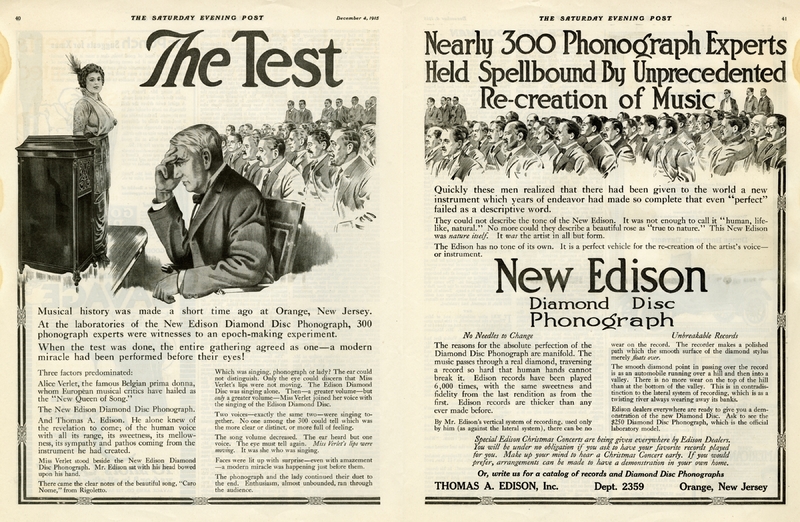

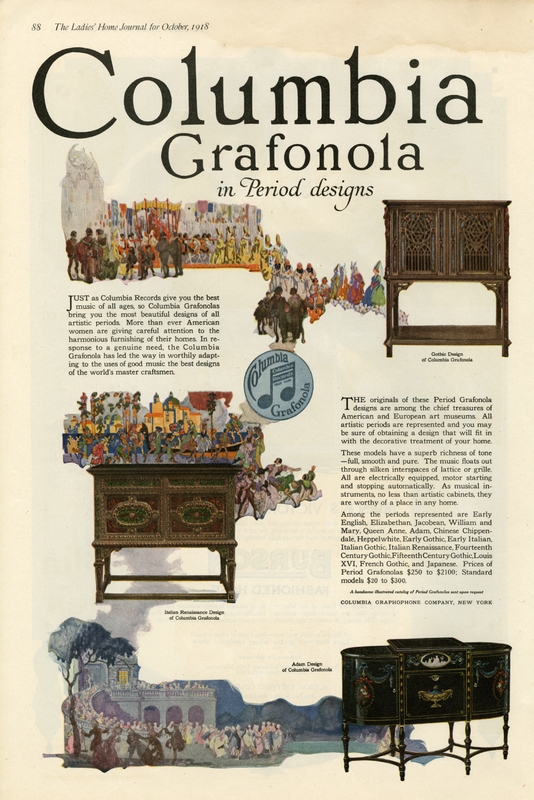

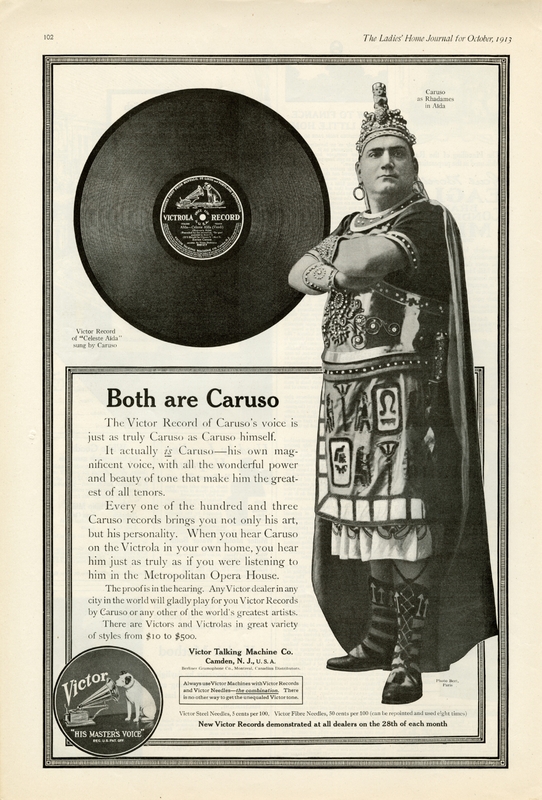

Another component of the Grinnell College Early Phonograph Collection is more than 150 period advertisements generated by the recording industry that were published in popular magazines of the day. In these we find frequent reference to “phonographs” as “instruments” or “musical instruments”, and of the life-like quality of the sound captured on recordings and reproduced on phonographs. Here are a few ads to illustrate these points (please read as much of their texts as possible):

Although the act of recording splits in time and in space a performance and its performers from its reception and its listeners (an arrangement that was not possible prior to the invention of the phonograph in 1877 and the establishment of the music recording industry in the 1890s), the early recording industry felt compelled to suggest, if not convince, its audience that the phonograph was simply a new variety of musical instrument and that the sounds that emanated from it possessed all the magic, power, and impact of music experienced as live performance.

These were not the only challenges faced by early recording companies. They also had to develop the means of making hundreds if not thousands of exact copies of a recorded performance while at the same time manufacturing and selling the equipment necessary for playing them back by huge numbers of consumers.

Certain advances in material science and record pressing had to fall into place before the recording industry could truly take off. Many of these advances took place a few years on either side of the year 1900. In the 1890s, most commercial releases were made on wax cylinders and discs (good for perhaps a few dozen playings before their encoded information wore away) that could not be used as a “master” from which countless “copies” could be generated. Before 1900 a method of creating a negative metal “stamp” of a wax-disc master recording had been developed, and advances were made in creating materials (at first, hardened wax, eventually, shellac, celluloid, and plastic) that, once stamped with a metal master, could be played many more times than copies made with soft waxes. By 1907, plastic compounds had been developed onto which the detailed soundwave patterns encoded on either a wax-disc master (for disc records) or wax cylinder master (for cylinders) could be transferred, using metal stamps (for discs) or metal molds (for cylinders), to hundreds of commercially saleable copies and, before long, descriptors such as “indestructible” started to appear on disc and cylinder packaging and in advertisements.

Equally as important for businesses in the early stages of development of the recording industry was to convince the public they needed to purchase a phonograph for their home. Most companies of the time had engineering departments that were constantly introducing new design innovations that ostensively improved the sound of their phonographs. This resulted, typically, in “lineages” of machines new models of which appeared on the market every several months or every few years. Some companies, such as Victor and Columbia, produced millions of phonographs in an amazing variety of models between 1900 and 1930. At any one time in these early decades of the recording industry, these manufacturers would have several models available to consumers at a variety of sticker prices. In 1898, when the oldest phonograph in Grinnell’s collection was produced—the Eagle—it could be purchased (without a case) with a single coin—a $10 U.S. gold coin called an “Eagle”. By 1918 when the below ad was released, Columbia (their tradenames for phonographs were “Graphophone” for external-horn machines, and “Grafonola” for internal-horn machines) was producing and selling models that cost as much as $2,100. At the same time, they were selling more modest models ranging in price from $20 to $300. Which model a consumer decided to buy for their use at home would, of course, depend in large part on their financial means, but expensive phonographs such as seen in the following ad could also be used by wealthy individuals to display their self-perceived social status to others.

Early recording companies in America and their affiliates in Western Europe were not satisfied with creating a market for captured sounds exclusively in America and Europe. Starting just after the turn of the 20th Century, companies such as Victor (and its European partner His Master’s Voice, or HMV) and Columbia mounted recording expeditions to the far corners of the world—East Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and South America—to record local performers. At first, record masters were shipped back to America and Europe for processing into phonograms before being shipped back to their place of origin for sale, but eventually regional pressing plants were set up around the world for the production of recordings for emerging markets of phonograph listeners outside of America and Western Europe. Thus, in a short period of time, listening to recorded music became a global phenomenon.

We now need to return to the two questions posed back at the beginning of this essay. The first, “Are phonographs musical instruments?”, can still be answered positively with the caveat that there is more than one type of musical instrument. Phonographs are musical instruments but different from the other musical instruments presented on this site. “Conventional” music instruments are objects with which their human operators produce sounds in real time. These objects transduce various forms of energy humanly applied to them by their performer to produce ephemeral qualities and patterns of sound deemed musical by the culture to which the instrument and its performer belong. Early phonographs are also musical instruments but ones with which their human operators reproduce previously performed live music the sound waves of which have been captured and transduced onto a physical device (a record or cylinder) that can be sounded at a distance in time and location from when the music was originally performed. But, in the end, they (“conventional” instruments and phonographs) both produce musical sounds.

The second question: “Are recorded performances equivalent to live performances?”, is more difficult to answer affirmatively. Any method and equipment of sound capture produce a result that in some way diverges from the sound a human ear receives while listening to live music. However marvelously ingenious and magical the technology of sound capture, its storage onto phonograms, and its playback on a phonograph was during the early decades of the recording industry, it is a far cry from the sound produced live in the recording studio or in a performance venue. If nothing else, the unavoidable surface noise produced by the contoured sides of a groove passing beneath a metal or gem-tipped stylus/needle is almost impossible not to notice. But there are other compromising matters that set the sound of a recording apart from what the human ear hears—early recordings have a narrower frequency range than does the human ear, making some instruments less suitable for recording than others (the most well-known example of this is the substitution in recording sessions of the double bass by the tuba; the latter was more easily captured by early equipment, the former could hardly be heard). Fortunately for singers, the early recording equipment captured the human voice quite well; brass and woodwind instruments also recorded well. Even with its obvious shortcomings, recording companies continuously pushed upon the public through their advertising the belief that the sound quality of their products was absolutely faithful to the sound quality of the artists they recorded when heard in live performance. This advertising strategy is no better illustrated than with the following ad that appeared in a 1913 issue of The Ladies’ Home Journal:

In closing, we will state that we have decided to include the phonographs found in the Grinnell College Music Department Early Phonograph Collection in this website as a particular variety of musical instrument that we will call stylusphones.

Additions to the Sachs-Hornbostel instrument classification system

Neither when the Sachs-Hornbostel numerical classification system was devised in 1914 nor when MIMO revised the system in 2011, were phonographs taken into consideration. Therefore, classification numbers have had to be created for these sound-producing instruments in order for them to be included in this musical instrument website. We could not find an already existing descriptor for phonographs in either previous system, so we have decided to call them “stylusphones” (meaning a vibrating stylus or needle is at the root of sound production on these instruments). Since both acoustic and electro-acoustic phonographs are found in the Grinnell Early Phonograph Collection, two sets of numerical code had to be created, one for the acoustic instruments, the other of the electro-acoustic phonographs. In an attempt to keep in style with the revised classification system published by MIMO, this is what we have devised [Note: only some of these classification numbers are needed and used for the phonographs in the Grinnell Collection]:

Acoustic phonographs

112 Indirectly struck idiophones: The player himself does not go through the movement of striking; percussion results indirectly through some other movement by the player. The intention of the instrument is to yield clusters of sounds or noises, and not to let individual strokes be perceived (from MIMO revision document)

112.5 idiophone—stylusphone: the vibrational device of the instrument is a stylus/needle excited indirectly with a phonogram containing a transduced analogue signal in the physical contours of its groove

112.51 idiophone--stylusphone with pointed metal stylus: the vibrational device of the instrument is a pointed metal stylus or needle

112.511 idiophone--stylusphone with pointed metal stylus mechanically linked to a membrane transducer: a small membrane mechanically linked to the stylus/needle transduces the vibration of the stylus/needle into audible sound

112.511.1 idiophone--stylusphone with pointed metal stylus, reproduction directed by external acoustical horn: the sound of the membrane transducer is directed and heard through an acoustical horn outside of the phonograph

112.511.2 idiophone--stylusphone with pointed metal stylus, reproduction directed by internal acoustical horn: the sound of the membrane transducer is directed and heard through an acoustical horn located inside the phonograph

112.52 idiophone--stylusphone with a glass- or gem-tipped metal stylus: the vibrational device of the instrument is a glass/gem-tipped metal stylus or needle

112.521 idiophone--stylusphone with a glass- or gem-tipped metal stylus linked to a membrane transducer: a small membrane mechanically linked to the stylus/needle transduces the vibration of the stylus/needle into audible sound

112.521.1 idiophone--stylusphone with a glass- or gem-tipped metal stylus, reproduction directed by external acoustical horn: the sound of the membrane transducer is directed and heard through an acoustical horn outside of the phonograph

112.521.2 idiophone--stylusphone with a glass- or gem-tipped metal stylus, reproduction directed by internal acoustical horn: the sound of the membrane transducer is directed and heard through an acoustical horn located inside the phonograph

Electro-acoustic phonographs

51 electrophone--electro-acoustic instruments and devices: Modules and configurations of acoustic, vibratory mechanisms and electronic circuitry such as transducers and amplifiers. The acoustic or mechanical vibration is transduced into an analogue fluctuation of an electrical current. All instruments built or structurally modified to deliver a signal to an amplifier and loudspeaker are classed as electrophones, even if they have some capability of sounding acoustically [from MIMO revision document]

511 electrophone--electro-acoustic idiophone: the source of vibration on an instrument is a solid but elastic material other than a stretched membrane or string; the produced mechanical vibration is transduced into an analogue electrical signal delivered to an amplifier and a loudspeaker

511.1 electrophone--indirectly-struck electro-acoustic idiophone: the player indirectly excites the vibrational device of the instrument

511.11 electrophone--indirectly-struck electro-acoustic idiophone stylusphone with gem-tipped stylus: the vibrational device of the instrument is a gem-tipped stylus or needle excited indirectly with a phonogram containing a transduced analogue signal in the physical contours of its groove

511.111 electrophone--indirectly-struck electro-acoustic idiophone stylusphone with a stationary gem-tipped stylus: the stylus is positioned in a phonogram groove and does not move; the groove, with its internal contours, moves beneath and excites the stylus

511.111.1 electrophone--indirectly-struck electro-acoustic idiophone stylusphone with a stationary gem-tipped stylus and internal loudspeaker: the transduced electrical signal from the stylus/needle is amplified and heard through a loudspeaker integral to the phonograph

511.112 electrophone--indirectly-struck electro-acoustic idiophone stylusphone with a mobile gem-tipped stylus: the stylus is positioned in and moves along a phonogram groove and its internal contours, exciting into vibration the stylus; the phonogram itself does not move

511.112.1 electrophone--indirectly-struck electro-acoustic idiophone stylusphone with a mobile gem-tipped stylus and internal loudspeaker: the transduced electrical signal from the stylus/needle is amplified and heard through a loudspeaker integral to the phonograph

The Grinnell College Music Department Early Phonograph Collection

Phonographs

At the outset of the consumer-oriented music industry, machines were mass produced to play one or the other of two distinct varieties of phonograms: cylinders and discs. Examples of both are found in this collection. From the 1890s through 1908, cylinder machines were designed to play only cylinders with a maximum duration of two minutes. In 1908, recording companies redesigned cylinders and their machines to accommodate cylinders with a maximum duration of four minutes. This was accomplished without changing the dimensions of the cylinder itself but by reducing the width of the groove in half (thereby doubling the number of times that it spirals around the cylinder surface from 100 per inch to 200 per inch but without changing the 160rpm rate of rotation of the cylinder), by changing the machining of the machine’s drive screw and/or gearing, and by using a soundbox with a smaller-diameter needle. All eight of the collection’s early machines (made between 1898 and 1918) are driven by spring motors and include no electronics.

Cylinder Machines

Machines that play two-minute cylinders

Two two-minute cylinder machines are found in the Grinnell collection. Both are external horn machines capable of playing standard size cylinders with 100 grooves per inch rotated at 160rpm.

Columbia Graphophone Type B Phonograph

Machines that play four-minute cylinders

Two four-minute cylinder machines are found in the Grinnell collection. One (the Edison Standard) is an external-horn machine, the other (the Edison Amberola) an internal-horn machine. Both play standard size cylinders with 200 grooves per inch rotated at 160rpm.

This machine, when new, could play either two-minute or four-minute cylinders by including two reproducers (one for the playing of two-minute cylinders, the other for four-minute cylinders) and a button switch the positioning of which had to be placed for the playing of either two-minute or four-minute cylinders (the position of this switch affects the gearing that drives the rate at which the stylus moves across the cylinder). The machine now only has the four-minute soundbox so is used only for playing four-minute cylinders.

Disc Machines

Four disc phonographs are found in the collection. Three of them play 78rpm discs (any diameter up to 12-inches; both one-sided and two-sided discs); one phonograph is exclusively used to play Edison ten-inch 80rpm Diamond Discs.

Machines that play 78rpm discs

Columbia Sterling B Phonograph

Machines that play 80rpm discs

Edison C-150 Diamond Disc Phonograph

Other machines (electro-acoustic phonographs)

Two additional phonographs are found in the collection, and both are electro-acoustic machines. One of these can play both 78rpm discs and micro-groove (long-playing) discs that rotate at either 45rpm or 33-1/3rpm. To do this, it has two styluses. This machine needs to be plugged into an electrical outlet to operate. The other electro-acoustic phonograph is a novelty machine both in shape and operation. Shaped like a Volkswagon bus, this battery powered phonograph does not include a turntable; rather, the micro-groove phonogram being played remains stationary while the phonograph itself moves round and round the disc with the machine’s stylus following the phonogram’s spiral groove.

Phonograms

As mentioned above, the Grinnell College Music Department Early Phonograph Collection includes hundreds of phonograms in a variety of formats. At the time this collection was gifted to the Music Department it included [click on the format to open its inventory of phonograms]:

55 10-inch 1-sided 78rpm discs

19 12-inch 1-sided 78rpm discs

316 10-inch 2-sided 78rpm discs

10 12-inch 2-sided 78rpm discs

43 10-inch 2-sided 80rpm Edison Diamond Discs

Several historically significant composers, conductors, and performers are heard on some of these 561 phonograms: John Philip Sousa conducting his band and the U.S. Marine Band performing marches he composed; Enrico Caruso singing; Serge Rachmaninoff, George Gershwin, and Bela Bartok performing on the piano (usually, but not always, their own compositions); Maurice Ravel conducting an orchestral performance of his work “Bolero”, and numerous other composers, musicians, conductors, and comedians well known during their lifetimes but not as well known today as the other names we’ve listed.

Period Advertisements

The early recording industry used advertisements published in popular magazines to persuade the general public that they needed to possess record players and phonograms in their homes. The Grinnell College Music Department Early Phonograph Collection includes, in addition to several period phonographs and hundreds of period phonograms, 160 advertisements that were created and published between 1897 and the early 1950s. While the bulk of these advertisements focus on record players, recordings, and recording artists during the formative years of the recording industry (roughly the first three decades of the 20th century), a few of the ads are for later technologies and equipment (home radios, tape recorders, and the introduction of long-playing micro-groove phonograms [33 1/3 rpm and 45 rpm disc formats] that would before long [by the end of the 1950s] end the 50-plus year reign of the 78-rpm formats). For an inventory of these ads (a few of which have been reproduced in this essay), click this link.

Reference Books

Barr, Steven C. 1992. The Almost Complete 78 RPM Record Dating Guide (II). Huntington Beach, CA: Yesterday Once Again.

Baumbach, Robert W. 2005. Look for the Dog: an illustrated guide to Victor Talking Machines. New rev. ed. Los Angeles: Mulholland Press. Inc.

Baumbach, Robert W. 2003. Victor Data Book. Los Angeles: Mulholland Press, Inc.

Braun, Hans-Joachim. 2002. Music and Technology in the Twentieth Century. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Davies, Hugh. 2002. “Electronic Instruments: Classifications and Mechanisms.” in Hans-Joachim Braun Music and Technology in the Twentieth Century. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 43-58.

Dethlefson, Ronald. 1997. Edison Blue Amberol Recordings: 1912-1914. 2nd ed. Woodland Hills, CA: Stationary X-Press.

Dethlefson, Ronald. 1999. Edison Blue Amberol Recordings Volume II: 1915-1929. 2nd ed. Woodland Hills, CA: Mulholland Press, Inc.

Fabrizio, Timothy C., and George F. Paul. 1997. The Talking Machine: an illustrated compendium, 1877-1929. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing Ltd.

Fabrizio, Timothy C., and George F. Paul. 2004. Phonographica: the early history of recorded sound observed. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing Ltd.

Fabrizio, Timothy C., and George F. Paul. 2007. A World of Antique Phonographs. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing Ltd.

Frow, George L. 2001. The Edison Disc Phonographs and the Diamond Discs. 1st American ed., newly rev. and enlarged. Los Angeles: Mulholland Press. Inc.

Frow, George L. 1994. The Edison Cylinder Phonograph Companion. 1st American ed., newly rev. and enlarged. Woodland Hills, CA: Stationary X-Press.

Gelatt, Roland. 1977. The Fabulous Phonograph, 1877-1977. First Collier Books ed. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc.

Goldsmith, Peter D. 1998. Making People’s Music: Moe Asch and Folkways Records. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Katz, Mark. 2010. Capturing Sound: how technology has changed music. Rev. ed. With compact disc. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press.

Kenney, William Howland. 1999. Recorded Music in American Life: the phonograph and popular memory, 1890-1945. New York: Oxford University Press.

Morton, David. 2000. Off the Record: the technology and culture of sound recording in America. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

Reiss, Eric L. 2003. The Compleat Talking Machine. 4th ed. Chandler, AZ: Sonoran Publishing, LLC.

Suisman, David. 2009. Selling Sounds: the commercial revolution in American music. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Weber, James N. 1997. The Talking Machine: the advertising history of the Berliner Gramophone & Victor Talking Machine. Eric Skelton, ed. Midland, Ontario: ADIO Inc.

Record Catalogs

Columbia Records: give music! December 1921.

Victor Records May 1913.